I spent the morning of May 25, 2020, thinking about race and policing in America. It was a little over a month since the launch of the daily news podcast I co-hosted at the time. We'd been stuck inside for twice as long, still unsure how much longer the coronavirus would make leaving the confines of our apartment a dangerous affair. The walls of my apartment felt oppressive but better than the alternative; New York City had climbed down from the horrifying peaks of April, but over a hundred people were still dying every day in overcrowded hospitals.

In the middle of all this death, Twitter had erupted the day before over a video taken in Central Park, just a few miles from where I was sitting. A white woman, later identified as Amy Cooper, was recorded calling the police on a Black birdwatcher named Christian Cooper for asking that she leash her dog. There was an "African American man threatening" her, she claimed in performative wailings. Given our mandate to combine hard news and internet culture, it felt like an easy way to get listeners to care about how dangerous police interactions can be for Black men.

"People have died in incidents like this," New Yorker staff writer Jelani Cobb, a Columbia University professor, told me and my co-host, Casey Rackham, in the segment we recorded that afternoon. Cobb recounted the story of John Crawford, who was shot while holding a BB gun at an Ohio Walmart, as an example of the danger Christian Cooper faced at the time. "It's not just a kind of abstract concern for Christian Cooper's well-being," he said.

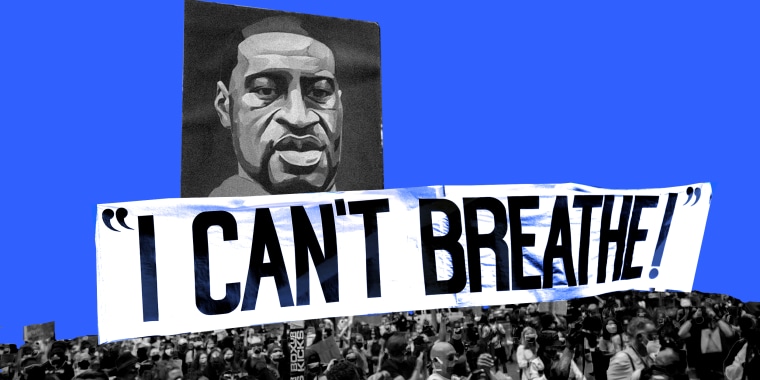

Three hours after the episode went live, George Floyd bought a pack of cigarettes at a grocery store in Minneapolis. Ninety minutes after that, he was pronounced dead, his last moments captured by a cellphone camera, Derek Chauvin's knee pressed firmly into his neck. "I can't breathe," he pleaded, echoing Eric Garner, echoing the patients in New York's hospitals, echoing our people.

That was Monday. The protests began too late for us to capture in the next day's episode — by Wednesday, we would cover them every day for the next two weeks as they spread across the country. It felt sharp and as unpredictable as lightning, a wild sort of power that could leave scars or act as a catalyst to permanent transformation.

One year later, I'm here in the same apartment, writing this, my little addition to the wave of tributes and memorials and retrospectives asking what has truly changed since then. It's a question that I was struggling with when I revisited the first podcast episode in which Casey and I discussed Floyd's death. At the time, I'd marveled to her that we'd started the week talking about birdwatching and racism, of all things:

And then, not 24 hours later, we have a situation where the police actively kill a person for no good reason. And it’s just ... I’m tired, Casey, man. I — we’re in the middle of so much right now, and the fact that we’re dealing with this, too? This 200-plus-year struggle, as we’re trying to survive and not die by virus. To have someone choking in the street on purpose by the people who are supposed to be protecting us, it’s almost too much.

I don't know for sure what, if any, broader societal ramifications Floyd's death will have. Chauvin's conviction was a case of the state's clearly naming what we all saw — the breath exiting our lungs was a sigh of relief, not a shout of hope and joy that change had come. The police reform bill named after Floyd is still in negotiations in the Senate over how much immunity should be granted to officers accused of misconduct. His family will meet with President Joe Biden on Tuesday in a symbolic consolation prize.

But I can say that in his murder, two things became clear to me. The first: The police will keep killing Black men for as long as they are given power and impunity to do so. The U.S. hit 100,000 confirmed coronavirus deaths the same week Floyd died. How does this not imbue some sense of duty in those sworn to safeguard us? It's no wonder the pressure caused a city, and a country, to explode.

Second: I soon realized that the callousness, the utter indifference to protecting life in the face of so much death, hit differently from what I'd felt before. Trayvon Martin's death shattered the delusion I'd crafted that I was different, that through my actions and nonthreatening demeanor I could somehow be spared the injustices heaped upon Black men. The Ferguson protests made it clear to me how invested the state was in keeping the status quo, its armored vehicles rolling out against unarmed protesters demanding the rights promised them at birth. I'd been saddened, dismayed, upset and distressed as the killings continued. But Floyd's murder gave me a permission that I'd never fully granted myself: to be angry.

Floyd’s murder gave me a permission that I’d never fully granted myself: to be angry.

Listening back, I'm surprised at how restrained the voice in my headphones sounds to me now. I can make out the spark of anguish in the words recorded off the cuff but not what was smoldering underneath, what had been slowly burning for years as the post-racial lie of my childhood had become more and more evident. The words tumble out in a rush, as if daring my lips to cut them off before they escape.

The man who spoke those words into a shotgun microphone wouldn't have written what I did last month after Daunte Wright joined the forever lengthening list of Black lives ended at the hands of the police. He's afraid of what it would mean to be so clearly invested in this narrative. He's afraid that if he starts to shout, he may never stop shouting. I may never stop shouting.

Too many things are exactly the same as they were when Floyd's face was pressed against the asphalt. But I'm different. It's not enough, not nearly enough. I can only hope that enough people out there are similarly changed to make it count, to see how much further we've gotten another year from now.