Women have played a pivotal role in the Central Intelligence Agency since it was established in 1947. And despite the agency’s efforts to hold them back, many women in the CIA found ways to work within – and expand – the confines of the roles which they were assigned to for decades. And as spies, they were attuned to many things men didn’t see, becoming some of the best operatives in the country.

That story is detailed in the new book “The Sisterhood: The Secret History of Women at the CIA” by award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author Liza Mundy.

In the book, Mundy tells the stories of three generations of women in the CIA. She draws on hundreds of interviews with key players, including current CIA employees. Know Your Value recently chatted with Mundy about the book.

Below is the conversation, which has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Know Your Value: Tell us about the genesis of the book and why you decided to write it now.

Liza Mundy: In many ways, “The Sisterhood” is a complement to my 2017 book, “Code Girls,” which tells the story of more than 10,000 young American women who travelled to Washington, D.C. during World War II, to break enemy codes. When I was writing “Code Girls,” I knew there was a parallel cohort of women spies—patriotic, resourceful women recruited for the wartime espionage effort at a time when the United States was desperately trying to upgrade our intelligence capabilities after the tragic surprise of Pearl Harbor. The most famous of these was Julia Child, but she had thousands of colleagues. I wanted to tell that story of women’s contributions to spycraft and to continue it, showing women’s role in Cold War espionage.

I have always been fascinated by how, after World War II, despite (or maybe because of) all women contributed to victory—not just Rosie the Riveter working in factories, building ships and bombers, but women who did codebreaking, early computer programming, and national security work—there was an effort to drive women out of the workplace and back into the homes. Let me tell you: that effort did not succeed, not wholescale, and not in the intelligence business. Many women stayed on the job. Everybody thinks all those Cold War spies, stealing secrets, holding clandestine meetings, risking their lives to avert nuclear war with the communist Soviet Union, were men—a whole CIA’s worth of James Bonds. Think again. Women made big intelligence wins during the Cold War, at huge personal sacrifice.

Know Your Value: In the book, you uncover the stories of women who made oftentimes hidden contributions to CIA history. Tell us about one or two of your favorite women who are highlighted in the book.

Mundy: Starting out, I wondered if I could find even a few women to talk. There turned out to be many—scores—and their stories were incredible.

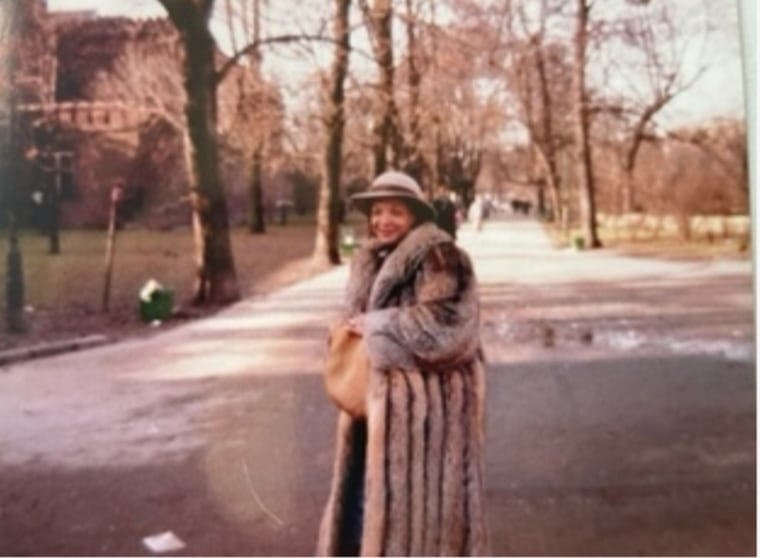

One of my favorites, though I sadly never got to meet her—she was going into the hospital for cancer treatment even as we were emailing to set up an appointment and did not survive—is Shirley Sulick. Shirley Sulick was the Black wife of Mike Sulick, a highly regarded, white clandestine officer who served in tough spots around the world, including Moscow. Like so many CIA wives, Shirley was instrumental to her husband’s career. Vivacious, loyal, and charismatic, she was an enormous help to Mike as he travelled around Moscow and its environs trying to elude surveillance and communicate with “assets”—Soviet officers passing secrets to the U.S. During the Cold War, spying in places like Moscow was surprisingly physical, in that it entailed throwing messages out of cars, leaving chalk marks, picking up “dead drops,” and jumping out of a car, maybe at a bend in the road where the KGB’s surveillance cars couldn’t see you. Shirley Sulick did all those things; she had a heavy foot on an accelerator and loved to take the KGB on merry chases. She also would carry huge purses, so she could bend over and sweep up a message while pretending she had dropped a lipstick or pencil. Shirley was also beloved by the wider CIA community, and provided comfort and solace to many officers during difficult periods…

Another favorite was Molly Chambers, who received a recruitment call in her sorority house at UC Davis, several years after the attacks of 9/11. She did not consider herself a super star, but rather, one of those who “showed up” to serve, after 19 hijackers transformed the world she would grow up in. Molly did counter-terrorism work in many African countries, and she also went after “hard targets” such as North Koreans, Chinese, and other adversary services. She was hilarious talking about getting naked massages from a potential source working at a spa run by North Koreans; giving him a computer thumb drive full of Keanu Reeves movies after learning he was a fan; flying back from Washington D.C. with a box of Georgetown cupcakes on her lap; whatever it took to “elicit” info.

She was also instrumental to a successful effort to find some of the Nigerian schoolgirls kidnapped by the terrorist group Boko Haram, and return them to their parents. She spoke about her work with honestly and vim, describing it as the hardest, and best, thing she has ever done. She also showed me some of the cool and classic implements of the trade, like fake passports and quick-change license plates. And, of course, sunglasses.

I could go on and on.

Know Your Value: What was the most surprising takeaway you found in your research?

Mundy: As a journalist who started work in the 1990s, I identified with some of the bias and discrimination the spies of the same era encountered. But I was surprised by what a treacherous workplace the CIA itself can be; the undermining that an officer must be on guard against, even from colleagues. Especially from colleagues. Often, an officer would say of a colleague, “He made a lot of enemies” or “She made a lot of enemies.” How often do you hear that in a workplace? I mean, colleagues spoken of as actual enemies? It went way beyond anything I had ever experienced at a newspaper. But it’s a competitive and elitist place. The CIA, after all, hires and looks for people comfortable with manipulation, propaganda and outright lying. So, I guess it’s no surprise that the same traits materialize at work.

I was also surprised by the number of women who, to get ahead, or simply to defend themselves against undermining efforts, had to run “operations” against the agency itself—and succeeded. Turns out that two can play that game.

Know Your Value: You note in the book that women were unlikely spies, which actually made them perfect in many ways for the role. Explain how gender oftentimes helped these women.

Mundy: For many years, men at the CIA—or some of them—argued that women were incapable of being effective spies, maintaining that women didn’t have the guts or moxie or, you know, balls, to ask a foreign national to hand over secrets. It’s similar to the old argument that women can’t be “rainmakers” on Wall Street or in law firms—that women can’t make the big ask. It was also believed that women would not be taken seriously in male-dominated countries and cultures—which, during the Cold War, was most cultures in the world.

But the women I interviewed showed just how wrong that thinking was; and how women brought their own skills and talents to spycraft. For one thing, women at the time (and to an extent, now) tended to be underestimated and inconspicuous, which made them much less likely to draw attention and made it easier for them to move unremarked on the street; or sitting in cars; or at restaurants. Being female, considered unimportant and not somebody to keep an eye on, turned out to be a huge asset and a great way to elude surveillance. When it comes to be surveilled, women are also better at spotting a tail, being more attuned to strangers in their personal space. Women are wary on the street, by nature and training.

Also, a big part of spying is taking care of an “asset”—the foreign national who is working for the CIA, passing secrets, often at great personal risk—and watching out for his or her well-being. As you can imagine, being an asset for the CIA is stressful and assets sometimes wobble or waver or lose heart. Women of course have many thousands of years of specialized training in taking care of people; and women, arguably, have the emotional intelligence to detect if something is wrong. In very male-dominated cultures, women spies found that men in that country were curious to meet them, and sometimes more likely to open up and show vulnerability when speaking to a woman officer.

And importantly, women spies looked around and understood that women secretaries and clerks, working for other countries, often had remarkable access to classified technology and files. And many of those same secretaries and clerks were pissed off about how they themselves were being treated. Revenge (like money) is a big inducement to hand over secrets. The women spies I interviewed were able to recruit women as assets and sources, and those women had a lot more access than the men they worked for realized.

Know Your Value: In the book, you also lay out how institutional sexism in the intelligence community at times hindered U.S. national security. Tell us about this – and do you think this institutional climate has gotten better for women who work in this industry?

Mundy: I started my research by interviewing the female analysts who had been paying close attention to Bin Laden and Al Qaeda years before the 9/11 attacks. Talking to them about why their warnings were ignored for so long, I realized that to truly understand this, I needed to understand how institutional sexism had been baked into the CIA from its inception in 1947. That’s when I began interviewing women who joined the spy trade in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. A pattern began to emerge, showing that women had been hired, but then deliberately—institutionally--channeled into certain niche offices and desks at the agency. I was blown away by their stories of outright discrimination, and the ingenious ways they overcame this.

I do think that the situation is better now; there has been one female CIA director, Gina Haspel. But it’s still very hard and very lonely, working in an isolated outpost in Kampala or Karachi, and it may be hard for women in ways that are different from men. Persuading your family to travel with you around the world is never easy, nor is it easy holding down a “day job” —your cover job—while doing your real work in secret meetings at night and on weekends. The work is consuming.

But let me also say this: Bringing women into the heart of the intelligence community is a big reason that the United States finally found and dealt with Osama Bin Laden. When I was beginning research on “The Sisterhood,” I also knew that in more modern times, a group of women were predicting the threat posed by Al Qaeda, long before the people at the top were willing to listen. This turned out to be true. Sexism is one reason why America was surprised on 9/11; and inclusion, even of a limited sort, is why America was able to track down perpetrators afterward. Women practically invented a new field called ‘targeting,” and were strikingly involved in the hunt for Osama bin Laden. Their patient and fierce efforts were a big reason that the CIA found him. It’s an argument for inclusion if there ever was one.